Price discrimination is a selling strategy that charges customers different prices for the same product or service, based on what the seller thinks they can get the customer to agree to. In pure price discrimination, the seller charges each customer the maximum price he or she will pay. In more common forms of price discrimination, the seller places customers in groups based on certain attributes and charges each group a different price.

Price discrimination is most valuable when the profit that is earned as a result of separating the markets is greater than the profit that is earned as a result of keeping the markets combined. Whether price discrimination works and for how long the various groups are willing to pay different prices for the same product depends on the relative elasticities of demand in the sub-markets. Consumers in a relatively inelastic submarket pay a higher price, while those in a relatively elastic sub-market pay a lower price.

[Important: Price discrimination charges customers different prices for the same products based on a bias toward groups of people with certain characteristics—such as educators versus the general public, domestic users versus international users, or adults versus senior citizens.]

With price discrimination, the company looking to make the sales identifies different market segments, such as domestic and industrial users, with different price elasticities. Markets must be kept separate by time, physical distance, and nature of use.

For example, Microsoft Office Schools edition is available for a lower price to educational institutions than to other users. The markets cannot overlap so that consumers who purchase at a lower price in the elastic sub-market could resell at a higher price in the inelastic sub-market. The company must also have monopoly power to make price discrimination more effective.

Price Discrimination under Monopoly

In monopoly, there is a single seller of a product called monopolist. The monopolist has control over pricing, demand, and supply decisions, thus, sets prices in a way, so that maximum profit can be earned.

The monopolist often charges different prices from different consumers for the same product. This practice of charging different prices for identical product is called price discrimination.

According to Robinson, “Price discrimination is charging different prices for the same product or same price for the differentiated product.”

According to Stigler, “Price discrimination is the sale of various products at prices which are not proportional to their marginal costs.

In the words of Dooley, “Discriminatory monopoly means charging different rates from different customers for the same good or service.”

According to J.S. Bains, “Price discrimination refers strictly to the practice by a seller to charging different prices from different buyers for the same good.”

Necessary Conditions for Price Discrimination

Price discrimination implies charging different prices for identical goods.

It is possible under the following conditions:

(i) Existence of Monopoly

Implies that a supplier can discriminate prices only when there is monopoly. The degree of the price discrimination depends upon the degree of monopoly in the market.

(ii) Separate Market

Implies that there must be two or more markets that can be easily separated for discriminating prices. The buyer of one market cannot move to another market and goods sold in one market cannot be resold in another market.

(iii) No Contact between Buyers

Refers to one of the most important conditions for price discrimination. A supplier can discriminate prices if there is no contact between buyers of different markets. If buyers in one market come to know that prices charged in another market are lower, they will prefer to buy it in other market and sell in own market. The monopolists should be able to separate markets and avoid reselling in these markets.

(iv) Different Elasticity of Demand

Implies that the elasticity of demand in the markets should differ from each other. In markets with high elasticity of demand, low price will be charged, whereas in markets with low elasticity of demand, high prices will be charged. Price discrimination fails in case of markets having same elasticity- of demand.

Types of Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is a common pricing strategy’ used by a monopolist having discretionary pricing power. This strategy is practiced by the monopolist to gain market advantage or to capture market position.

- Personal

Refers to price discrimination when different prices are charged from different individuals. The different prices are charged according to the level of income of consumers as well as their willingness to purchase a product. For example, a doctor charges different fees from poor and rich patients.

- Geographical

Refers to price discrimination when the monopolist charges different prices at different places for the same product. This type of discrimination is also called dumping.

- On the basis of use

Occurs when different prices are charged according to the use of a product. For instance, an electricity supply board charges lower rates for domestic consumption of electricity and higher rates for commercial consumption.

Conditions for Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is possible under the following conditions:

- The seller must have some control over the supply of his product. Such monopoly power is necessary to discriminate the price.

- The seller should be able to divide the market into at least two sub-markets (or more).

- The price-elasticity of the product must be different in different markets. Therefore, the monopolist can set a high price for those buyers whose price-elasticity of demand for the product is less than 1. In simple words, even if the seller increases the price, such buyers do not reduce the purchase volume.

- Buyers from the low-priced market should not be able to sell the product to buyers from the high-priced market.

Hence, we can conclude that a monopolist who employs price discrimination, charges a higher price from the market with inelastic demand. On the other hand, the market which is more responsive is charged less.

Difference between price discrimination and product differentiation

- Charging different prices for similar goods is not pure price discrimination

- Product differentiation gives a supplier greater control over price and the potential to charge consumers a premium price arising from differences in the quality or performance of a product.

Degrees of Price Discrimination

Prof. Pigou in his Economics of Welfare describes three degrees of discriminating power which a monopolist may wield. The type of discrimination discussed above is called discrimination of the third degree. We explain below discrimination of the first degree and the second degree.

Discrimination of the First Degree (1st) or Perfect Discrimination

Discrimination of the first degree occurs when a monopolist charges “a different price against all the different units of commodity in. such wise that the price exacted for each was equal to the demand price for it and no consumer’s surplus was left to the buyers.”

Joan Robinson calls it perfect discrimination when the monopolist sells each unit of the product at a separate price. Such discrimination is possible only when consumers are sold the units for which they are prepared to pay the highest price and thus they are not left with any consumer’s surplus.

For perfect price discrimination, two conditions are required

(1) To keep the buyers separate from each other, and

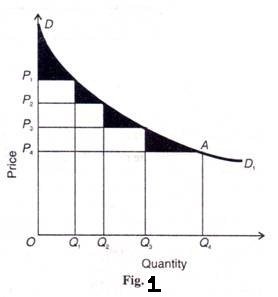

(2) To deal with each buyer on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. When the discriminator of first degree is able to deal with his customers on the above basis, he can transfer the whole of consumers’ surplus to himself. Consider Figure 1. Where DD1 is the demand curve faced by the monopolist. Each buyer is assumed as a price-taker. Suppose the discriminating monopolist sells four units of his product at four different prices:

OQ1 unit at OP1price, Q1Q2 unit at OP2 price, Q2Q3 unit at OP3 price and Q3Q4 unit at OP4 price. The total revenue (or price) obtained by him would be OQ4 AD. This area is the maximum expenditure that the consumers are willing to incur to buy all four units of the product under the first-degree discriminator’s all-or-nothing offer. But with no price discrimination under simple monopoly, the monopolist would sell all four units at the uniform price OP4 and thus obtain the total revenue of OQ4AP4.

This area represents the total expenditure that consumers would actually pay for the four units. Thus the difference between what Quantity the consumers were willing to pay (OQ4 AD) under Fig. 1 the take-it-or-leave-it offer of the first degree discriminator and what they actually pay (OQ4AP4) to the simple monopolist, is consumers’ surplus. This is equal to the area of the triangle DAP4.

Thus under the first-degree price discrimination, the entire consumers’ surplus is pocketed by the monopolist when he charges a separate price for each unit of the product. Price discrimination of the first degree is rare and is to be found in such rare products as diamonds, jewels, precious stones, etc. But a monopolist must have full knowledge of the demand curve faced by him and he should know the maximum price that the consumers are willing to pay for each unit of the product he wants to sell.

Discrimination of the Second Degree (2nd) or Multi-part Pricing

In discrimination of the second degree, the monopolist divides the consumers in different slabs or groups or blocks and charges different prices for different slabs of the same product. Since the earlier units of the product have more utility for the consumers than the later ones, the monopolist charges a higher price for the former units and reduces the price for the later units in the respective slabs.

Such discrimination is only possible if the demand of each consumer below a certain maximum price is perfectly inelastic. Electric supply companies in developed countries practice discrimination of the second degree when they charge a high rate for the first slab of kilowatts of electricity consumed. As more electricity is used, the rate falls with subsequent slabs.

Figure 2 illustrates the second degree discrimination, where DD1is the demand curve for electricity on the part of domestic consumers in a town. CP3 represents the cost of generating electricity, so that the electricity company charges M1P1 rate per kw. up to OM1 units. For consuming the next M1 to М2 units, the rate is lowered to M2P2. The lowest rate charged is M3P3 for M2 to M3 units. M3P3 is, however, the lowest rate which will be charged even if a consumer consumes more than M3 units of electricity.

If the electricity company were to charge only one rate throughout, say M3P3the total revenue would not be maximized. It would be OCP3 M3But by charging different rates for different unit slabs, it gets the total revenue equal to OM3 x P1M1 + OM2 x P2M2 + OM3x P3M3 Thus the second degree discriminator would take away a part of consumers’ surplus covered by the rectangles ABEP1and BCFP2 .The shaded area in three triangles DAP1 Р1ЕР2, and P2FP3 still remains with consumers as their surplus.

The second degree price discrimination is practised by telephone companies, railways, companies supplying water, electricity and gas in developed countries where these services are available in plenty. But it is not found in developing countries like India where such services are scarce.

The differences between the first and second degree price discrimination may be noted. In the first degree discrimination, the monopolist charges a different price for each different unit of the product. But in second degree discrimination, a number of units in one slab (or group or block) are sold at the lowest price and as the slabs increase, the prices charged by the monopolist are lowered. In the case of the former the monopolist takes away the whole of consumers’ surplus. But in the latter case, the monopolist takes away only a portion of the consumers’ surplus and the other portion is left with the buyer.

Conditions under which Price Discrimination is Possible

Price discrimination is possible under following conditions:

- Nature of Commodity

In the first place it is said that price discrimination is possible when the nature of the commodity or service is such that there is no possibility of transference from one market to the other.

That is, the goods sold in the cheaper market cannot be resold in the dearer market; otherwise the monopolist’s purpose will be defeated.

- Distance of Two Markets

Price discrimination is possible when the two markets or markets are separated by large distance or tariff barriers, so that it is not possible to transfer goods from a cheaper market to dearer markets. For instance, a monopolist may sell the same product at a higher price in Bombay and lower price in Meerut.

- Ignorance of the Consumers

Price discrimination is possible when the consumers are ignorant about price discrimination, they are not aware that in one part of the market prices are lower than in the other part. Thus, he purchases in dearer market, than in cheaper market since he is ignorant of the prices that are prevailing in different markets.

- Government Regulation

Price discrimination occurs when the government rules and regulations permit. For instance, according to rules, electricity rates are fixed at higher level for industrial purposes and lower for domestic uses. Similarly, railways charge by law higher fares from first class passengers than from the second class passengers. Hence, price discrimination is possible because of legal sanction.

- Geographical Discrimination

Price discrimination may be possible on account of geographical situations. The monopolist may discriminate between home and foreign buyers by selling at lower price in the foreign market than in the domestic market. Geographical discrimination is possible because no unit of the commodity sold in one market can be transferred to another.

- Difference in Elasticity of Demand

A commodity may have different elasticity of demand in different markets. Thus, the market of a commodity can be separated on the basis of its elasticity of demand.

Hence, a monopolist can charge different prices in different markets classified on the basis of elasticity of demand, low price is charged where demand is more elastic and high price in the market with the less elastic demand or inelastic demand.

- Artificial Difference between Goods

A monopolist may create artificial differences by presenting the same commodity under different names and labels, one for the rich and snobbish buyers and the other for the ordinary customers. For instance, a biscuit manufacturer may wrap small quantity of the biscuits, give it separate name and charge a higher price. Thus, he may charge different price for substantially the same product. He may charge Rs. 2/- for 100 gram wrapped biscuits and Rs. 1.50 for unwrapped biscuits.

Demand and Revenue under Monopoly:

In monopoly, there is only one producer of a product, who influences the price of the product by making Change m supply. The producer under monopoly is called monopolist. If the monopolist wants to sell more, he/she can reduce the price of a product. On the other hand, if he/she is willing to sell less, he/she can increase the price.

As we know, there is no difference between organization and industry under monopoly. Accordingly, the demand curve of the organization constitutes the demand curve of the entire industry. The demand curve of the monopolist is Average Revenue (AR), which slopes downward.

AR curve of the monopolist:

In Figure-9, it can be seen that more quantity (OQ2) can only be sold at lower price (OP2). Under monopoly, the slope of AR curve is downward, which implies that if the high prices are set by the monopolist, the demand will fall. In addition, in monopoly, AR curve and Marginal Revenue (MR) curve are different from each other. However, both of them slope downward.

The negative AR and MR curve depicts the following facts:

- When MR is greater than AR, the AR rises

- When MR is equal to AR, then AR remains constant

iii. When MR is lesser than AR, then AR falls

Here, AR is the price of a product, As we know, AR falls under monopoly; thus, MR is less than AR.

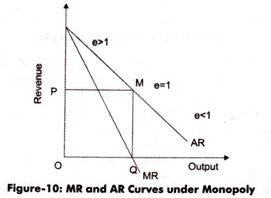

AR and MR curves under monopoly:

In figure-10, MR curve is shown below the AR curve because AR falls.

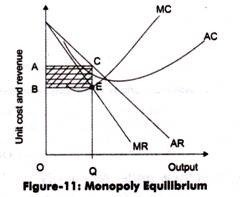

Monopoly Equilibrium:

Single organization constitutes the whole industry in monopoly. Thus, there is no need for separate analysis of equilibrium of organization and industry in case of monopoly. The main aim of monopolist is to earn maximum profit as of a producer in perfect competition.

Unlike perfect competition, the equilibrium, under monopoly, is attained at the point where profit is maximum that is where MR=MC. Therefore, the monopolist will go on producing additional units of output as long as MR is greater than MC, to earn maximum profit.

Monopoly equilibrium through Figure-11:

In Figure-11, if output is increased beyond OQ, MR will be less than MC. Thus, if additional units are produced, the organization will incur loss. At equilibrium point, total profits earned are equal to shaded area ABEC. E is the equilibrium point at which MR=MC with quantity as OQ.

It should be noted that under monopoly, price forms the following relation with the MC:

Price = AR

MR= AR [(e-1)/e]

e = Price elasticity of demand

As in equilibrium MR=MC

MC = AR [(e-1)/e]

Short-Run and Long-Run View under Monopoly:

Till now, we have discussed monopoly equilibrium without taking into consideration the short-run and long- run period. This is because there is not so much difference under short run and long run analysis in monopoly.

In the short run, the monopolist should make sure that the price should not go below Average Variable Cost (AVC). The equilibrium under monopoly in long-run is same as in short-run. However, in long-run, the monopolist can expand the size of its plants according to demand. The adjustment is done to make MR equal to the long run MC.

In the long-run, under perfect competition, the equilibrium position is attained by entry or exit of the organizations. In monopoly, the entry of new organizations is restricted.

The monopolist may hold some patents or copyright that limits the entry of other players in the market. When a monopolist incurs losses, he/she may exit the business. On the other hand, if profits are earned, then he/she may increase the plant size to gain more profit.